The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report came out on Monday. This post includes some background on the IPCC, and discussion of the report.

via libcom.org

The IPCC – background and history

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an international scientific collaboration – the largest of its kind – established under the auspices of the United Nations. It was founded in 1988 under the World Meteorological Organisation and the United Nations Environment Program, and later endorsed through the UN general assembly. The IPCC serves to systematically review and synthesise the current state of knowledge regarding climate change, and thus represents the benchmark of the scientific consensus. Work for the IPCC is on a voluntary basis, but caries a lot of prestige in the scientific community.

The consensus has been steadily strengthening as scientific evidence accumulates – and of course, as the climate warms, confirming and refining climate models. The First Assessment Report (FAR; 1990) found that greenhouse gases were ‘capable of’ warming the climate. In 1995’s Second Assessment Report (SAR), this was upgraded to a ‘discernible influence’. By the TAR (2001), this became ‘likely due to human activities’. AR4 – the naming convention changed, since ‘FAR’ was taken by the first one – further upgraded this to ‘very likely’. Then the first part of AR5, released last year, again upgraded this to ‘extremely likely’.

The IPCC is formed of three working groups, each of which produces a report. Working Group I deals with the physical science basis, Working Group II deals with impacts and adaptation, while Working Group III deals with mitigation (avoiding climate change). Once all three reports are out, a Synthesis Report is also produced. Monday’s report was from WGII, the working group that most heavily draws on economics, and is therefore the most open to social criticism (we touched on this in ‘Let them eat growth‘).1 Before we discuss the WGII AR5 report, we’ll briefly highlight two well-established criticisms of the IPCC.

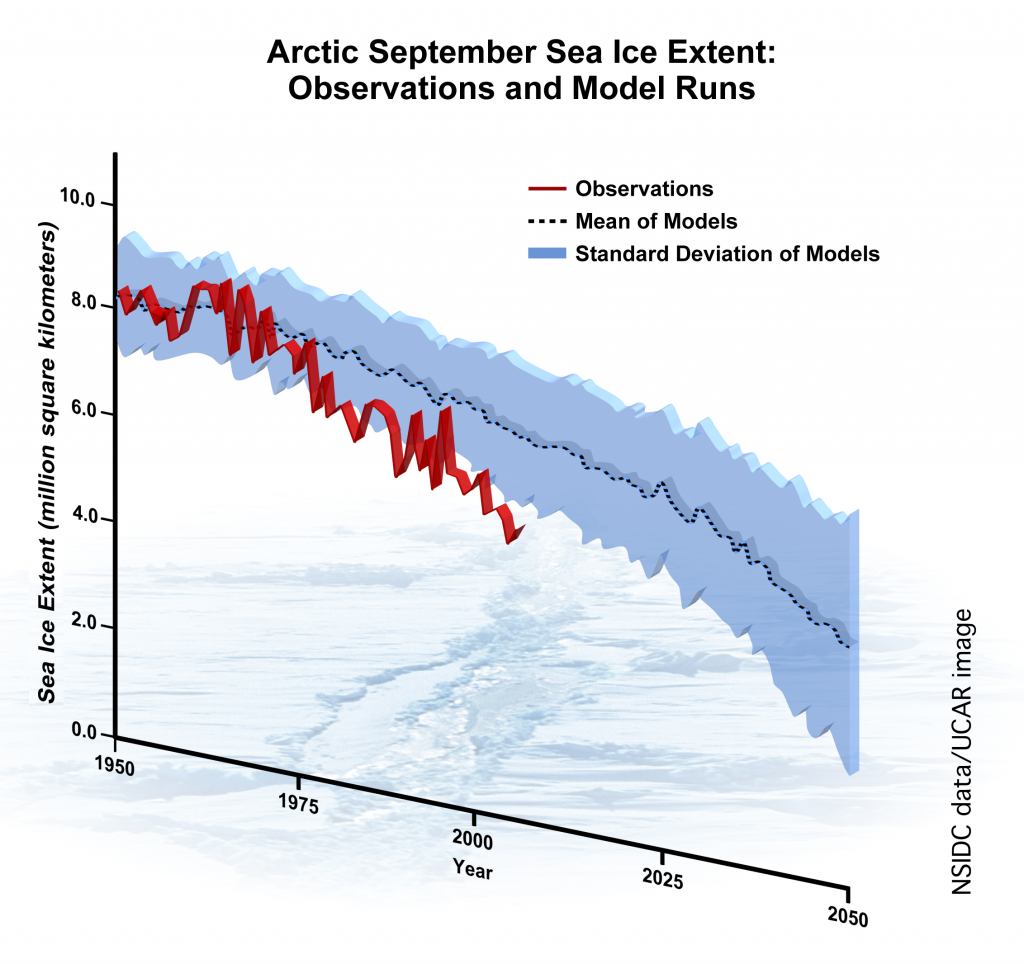

First, as a consensus-based body, the IPCC is inherently conservative. The ‘Summary for Policymakers’ in each report has to be agreed line-by-line by representatives of each participating state (typically more than 120). While this avoids controversy, it also neglects outlying views and, due to submission deadlines and lengthy process, excludes the latest research. As the latest research tends to be worse news, the consensus tends to be on the conservative side, and lag behind the cutting edge.2 For instance, the IPCC has consistently underestimated sea ice loss, with the real figures tracking beyond the lower limit of the projected range.

Arctic sea ice projections (blue) and observations (red). Source.

Second, the IPCC is bound by its mandate to be ‘policy relevant but not policy prescriptive’. Essentially, this is an apolitical mandate, yet the science shows overwhelmingly that business-as-usual is incompatible with stated climate change goals (like limiting warming to 2 degrees on pre-industrial levels). The IPCC’s inherent conservatism is thus confounded by a diplomatic quietism. They have typically walked this tightrope by producing scenarios, which show that current policies are on course for disaster and alternatives are needed, without being too prescriptive about what those alternatives are. Most recently, this has involved ‘representative concentration pathways’ (RCPs), which are policy-agnostic. There’s some good criticism of the RCP’s ’emissions budget’ from David Spratt here:

David Spratt wrote:

Unfortunately, because many people think if you have a budget you should spend every last dollar, the “carbon budget” message could be interpreted as saying there is plenty of budget left to spend.

However, these general criticisms shouldn’t take away from the fact the IPCC’s reports are the most important pieces of climate science literature, synthesising a vast amount of published research.

The latest report

Having read through the Summary for Policymakers of the latest report (SPM – the full report is not available yet), five things stand out.

1. A refreshing humility. Contrary to caricature of both scientific and economic pronouncements, the report acknowledges some of the more common technocratic pitfalls. First, there is an explicit acknowledgement that:

…indigenous, local, and traditional knowledge systems and practices, including indigenous peoples’ holistic view of community and environment, are a major resource for adapting to climate change.

Second, the SPM acknowledges the limits of economic costing, “because many impacts, such as loss of human lives, cultural heritage, and ecosystem services, are difficult to value and monetize.” While the framing of ecosystems as ‘services’ does itself presume an economic model, this is an important caveat to the figures that follow. Third, the SPM notes the wide range of economic forecasts is influenced by the wide range of ‘discount factors’. This is important, since discount factors, used by economists to value future costs/benefits, often introduce circular reasoning: a high discount factor is used, this makes future costs look small, which in turn makes carrying on as if the future doesn’t matter appear rational.3

2. Five ‘Reasons For Concern’ (RFCs). AR5 WGII distils the bad news of climate change impacts into five key points. While the buzzfeed brevity is clearly aimed at policymakers’ desire for executive summaries of executive summaries, this does summarise a huge, complex body of literature. The five RFCs are: unique and threatened systems (particularly Arctic sea ice and coral reefs); extreme weather events (including heat waves, extreme precipitation, and coastal flooding); distribution of impacts (particularly regarding crop production and uneven development); global aggregate impacts (the economic and biodiversity impacts of numerous combined trends); and, large-scale singular events (specific impacts associated with crossing irreversible tipping points, such as ice sheet loss and subsequent sea level rises). For this, the IPCC has been accused of ‘alarmism’, but if it’s alarming, that’s because the consequences of business as usual are really that bad. If anything, the RFCs are framed in very dry technocratic terms considering they describe war, famine, drought, mass displacement, and ecosystem collapse.

3. Intersectionality. The SPM endorses an explicitly intersectional approach to impacts and vulnerability. Cynically, the emphasis on complex multicausality could be seen as a way to sidestep criticising capitalism (which would violate the IPCC’s apolitical remit). But generally this emphasis is to be welcomed. The report talks about:

…intersecting social processes that result in inequalities in socioeconomic status and income, as well as in exposure. Such social processes include, for example, discrimination on the basis of gender, class, ethnicity, age, and (dis)ability.4

We could probably make a distinction between a technocratic or problem-solving intersectionality, which takes these processes as a given, and a critical intersectionality, which emphasises the social struggles around their (re)production.5 This has practical implications: the former tends to see the solution as more ‘freedom, equality, property, and Bentham’, whereas the latter would emphasise how these exclusions and hierarchies are mutually reproducing under capitalist conditions.6 This brings us to one of the SPM’s shortcomings:

4. Linking poverty reduction to economic growth. The SPM links slowing economic growth due to climate change to increased difficulties in poverty reduction. This repeats the commonplace but utterly wrong received wisdom of trickle-down economics and the Kuznets Curve. Thomas Piketty’s recently published analysis of inequality is emphatic that the trend is towards increasing polarisation and relative pauperisation, with brief reversals in the 20th century due to exceptional factors:

Piketty, Capital in the 21st century, p.15 wrote:

The sharp reduction in income inequality that we observe in almost all the rich countries between 1914 and 1945 was due above all to the world wars and the violent economic and political shocks they entailed (especially for people with large fortunes). It had little to do with the tranquil process of intersectoral mobility described by Kuznets.7

In addition to this, Beverly Silver’s analysis of the auto sector has demonstrated comprehensively that locally improving conditions have been closely linked to the level of class struggle. That said, the report stresses that climate change will disproportionately impact the already poor and marginalised, so the headline conclusion that climate change is bad news for poverty reduction stands.

5. Resilience. Finally, the report gives a useful definition of resilience, a term which is becoming increasingly contested.

IPCC WGII AR5 wrote:

The capacity of social, economic, and environmental systems to cope with a hazardous event or trend or disturbance, responding or reorganizing in ways that maintain their essential function, identity, and structure, while also maintaining the capacity for adaptation, learning, and transformation.

The term comes from ecology, but is undergoing significant recuperation and incorporation into state policy. This definition shows why: states stress the conservative aspect of ‘maintain their essential function’, whereas ecologists (and maybe radicals) stress ‘the capacity for adaptation, learning, and transformation’. One critic points out how the state use of resilience amounts to insisting that we continuously put up with bad things, essentially ‘keep calm and carry on’. But this recuperative meaning does not exhaust the concept, and the capacity for social transformation under adverse conditions is surely central to the question of climate change.

Meanwhile…

…US Secretary of State John Kerry has been warning that climate change inaction will be catastrophic – while the US pushes ahead with the Keystone XL project to further ramp up unconventional fossil fuel production. Statesmen see catastrophe on the horizon – and accelerate. No mountain of scientific consensus will change that, only the blocking of fossil-fuel based development.

- 1. Richard Tol, who we criticised in ‘Let them eat growth’, asked for his name to be removed from AR5 WGII, accusing the IPCC of ‘alarmism’. More generally, we’re assuming a critical realist stance here: scientific knowledge is socially constructed but relates to a reality which is independent of human thought. The physical sciences certainly describe this reality and thus have a good claim to universality, whereas economics tends to confuse/conflate features of specifically capitalist society with universal facts of nature. This is not to say physical science is beyond social critique (we’ll discuss this in future blogs), only that in critical realist terms, the object of the physical sciences is intransitive (independent of social construction), whereas for economics it’s transitive, since economics deals with social relations and emergent social forms.

- 2. Some see this as a strength however, as only well-established research is included, giving time for misleading results to be found out and shaky conclusions to be criticised.

- 3. This is not to say discount factors are not useful. They can model economic actors’ actual behaviours: indeed, corporate actors especially do operate on a very short-term horizon – that’s one reason we’re in this mess. The problem comes when there’s a circular movement between the descriptive and normative domains: when what is the case is used to determine what ought to be the case.

- 4. It should go without saying the UN’s take on class is not Marxist or libertarian communist.

- 5. In other words, acknowledging that inequality exists is not the same as analysing the power relations which (re)constitute it.

- 6. For an example of critical intersectionality, see Jasbir Puar’s argument that limited inclusion – e.g. gay marriage – for ‘homonationalist’ gays has simultaneously meant the exclusion and pathologisation of the Muslim ‘other’ in the War on Terror. In a specifically climate change context, Adrian Parr’s Wrath of capital is a good example, insisting on the importance of class relations without excluding analysis of gender, race, and other social forces.

- 7. Piketty is a social democrat who likes to stress that Marx was wrong, but he has assembled a vast amount of useful economic data (which suggests otherwise).